Voting Rights Act of 1965

The Voting Rights Act of 1965 (42 U.S.C.A. § 1973 et seq.) prohibits the states and their political subdivisions from imposing voting qualifications or prerequisites to voting, or standards, practices, or procedures that deny or curtail the right of a U.S. citizen to vote because of race, color, or membership in a language minority group. A product of the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s, the Voting Rights Act has proven to be an effective, but controversial, piece of legislation. It is considered one of the most far-reaching pieces of civil rights legislation in U.S. history.

The Voting Rights Act of 1965 (42 U.S.C.A. § 1973 et seq.) prohibits the states and their political subdivisions from imposing voting qualifications or prerequisites to voting, or standards, practices, or procedures that deny or curtail the right of a U.S. citizen to vote because of race, color, or membership in a language minority group. A product of the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s, the Voting Rights Act has proven to be an effective, but controversial, piece of legislation. It is considered one of the most far-reaching pieces of civil rights legislation in U.S. history.

The Voting Rights Act of 1965 grew out of both public protest and private political negotiation. Starting in 1961, nonviolent demonstrations were held in Georgia and Alabama. The hope of organizers was to attract national media attention and pressure the U.S. government to protect the constitutional rights of blacks. Newspaper photos and TV broadcasts of Birmingham’s racist police commissioner, Eugene Connor, and his men violently attacking protesters with water hoses, police dogs, and nightsticks awakened the consciences of whites.

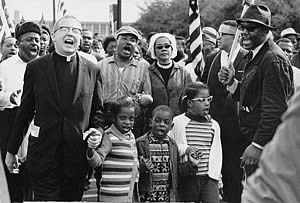

Selma, Alabama was the site of the next campaign. In the first three months of 1965, local residents and visiting volunteers held a series of marches demanding an equal right to vote. The demand of Dr. Martin Luther King JR. and other civil rights supporters for voting rights led to police violence and the murder of several marchers. Several marchers were imprisoned.

Selma, Alabama was the site of the next campaign. In the first three months of 1965, local residents and visiting volunteers held a series of marches demanding an equal right to vote. The demand of Dr. Martin Luther King JR. and other civil rights supporters for voting rights led to police violence and the murder of several marchers. Several marchers were imprisoned.

In the worst attack on Sunday, March 7 a group of 600 people were beaten by white state troopers and local sheriff’s deputies. They used billy clubs, whips, and tear gas against the peaceful marchers. The attack took place on the Edmund Pettus Bridge. At the time the nation was watching. Activist Amelia Boynton Robinson was brutally beaten by Alabama state troopers and the photo of that drew national attention to the cause and captured the brutality of the struggle for African American voting rights. A week after Bloody Sunday in Selma, President Lyndon Johnson gave a televised speech before Congress in which he denounced the assault.

President Johnson made civil rights one of his administration’s top priorities and used his formidable political skills to pass the Twenty-Fourth Amendment which outlawed poll taxes in 1964.

Although opposed by politicians from the Deep South, the Voting Rights Act was passed by large majorities in the House of Representatives (333 to 48) and the Senate (77 to 19). It was signed into law on August 6, 1965.

The Act empowered the federal government to oversee voter registration and elections in counties that had used tests to determine voter eligibility or where registration or turnout had been less than 50 percent in the 1964 presidential election. It also banned discriminatory literacy tests and expanded voting rights for non-English speaking Americans.

The original act was directed at seven southern states – Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Virginia – who were using poll taxes, literacy tests, and other devices to obstruct registration by African Americans. Among other things, the act required the seven states to obtain “preclearance” from the Justice Department or the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia before making changes in the electoral system.

Most provisions in the Voting Rights Act of 1965, and specifically the portions that guarantee that no one may be denied the right to vote because of his or her race or color, are permanent. Some enforcement-related provisions have required reauthorization over the years.

As a result, the Voting Rights Act was extended in 1970, 1975, and 1982. There were 3 enforcement-elated provisions set to expire in August 2007 but they were extended for another 25 years with a July 2007 reauthorization vote.